Japanese Ceramics

Highly skilled Japanese artisans have been producing exquisite Ceramics using a variety of techniques and in widely differing styles for many centuries. Their innovative and highly artistic output, often of...

Highly skilled Japanese artisans have been producing exquisite Ceramics using a variety of techniques and in widely differing styles for many centuries. Their innovative and highly artistic output, often of staggering quality, has always been greatly treasured not only within the domestic market but also by collectors and connoisseurs worldwide.

Early porcelain from the Arita, Nabeshima, Hirado and Kutani kilns together with the refined outputs of the Kakiemon family found a ready market in the country houses of the European nobility. These early porcelains from the 17th and 18th centuries, often of impressively large size, form a specialist collecting field of their own ,but latterly it is the truly breath-taking and superbly enamelled Meiji period earthenware known as “Satsuma” that has come to be the most coveted and highly collected of all Japanese ceramics.It is for this reason that we concentrate our article on Satsuma earthenware although most of the tips and advice in this section would apply equally across the entire spectrum of Japanese ceramics.

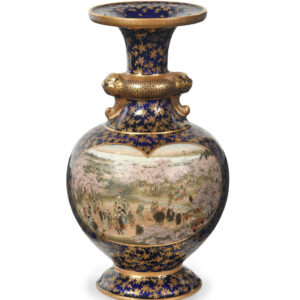

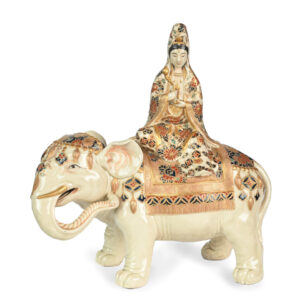

From a purely technical point of view Japanese “Satsuma” can be described as a dense cream coloured earthenware body having a fine and even crackle glaze usually decorated in over-glaze enamels. From an artistic point of view it could easily be described as the most intricate enamelled ceramic ever made by man. As the name suggests it was originally produced in the Province of Satsuma under the patronage of the Shimazu family who had been the Daimyo there since 1615.

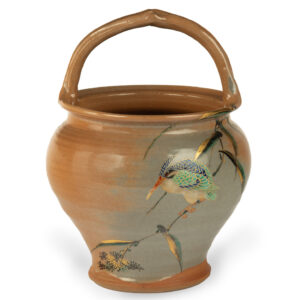

Its evolution into the finely decorated items that are nowadays so popular with discerning collectors did not really commence until the mid 19th century and subsequently developed rapidly during the Meiji period. Prior to that Satsuma ware enjoyed a reputation as a fine quality but frequently undecorated glazed earthenware aimed at the Japanese domestic market. However the aforesaid Daimyo of Satsuma, generally regarded as the most powerful at the time, was instrumental in Japan exhibiting at the first World Fair – the Paris Exposition in 1867 – and this naturally ensured a substantial display of high quality ceramics from his home Province. This proved to be a strong catalyst for innovation in production, design and artistic quality.

Japanese art including ceramics unsurprisingly received worldwide acclaim at the Paris Fair and indeed at subsequent exhibitions. This and several other factors quickly contributed to an explosion of interest in the “never before seen” art form that is Satsuma earthenware. Thankfully the Meiji Emperor was a great patron of Japanese Arts in all their various forms and quickly realised that the foreign currency flowing into the country from the sale of these works would greatly assist in his modernisation programme. Also many high ranking foreign advisors and their supporting workforces together with a high number of curious and wealthy early tourists were now in Japan. Satsuma ware with its developing designs and superb artistry appealed greatly to this new customer base and demand grew strongly. The continued involvement of the astute and powerful Shimazu family gave further impetus to its production.

Artistic Development

The development of Satsuma progressed hand in hand with the rapid modernisation of Japan during the Meiji period.

Early functional domestic pieces often with little or no decoration quickly evolved into a wider range of items of all shapes and sizes. Bowls, koro, vases, and boxes all became subjects for unbelievably intricate and detailed enamelling. They were adorned with finely painted and often idealised scenes from nature or rural everyday life, historical and legendary events, famous places, in fact anything that was shown to appeal to the insatiable foreign market now established both in Japan and worldwide. The lavish use of high quality gilding gave items a rich and sumptuous appearance. Decorative borders became an art form in their own right again displaying brocades, floral and other designs in a detail that defies belief.

Such was the success of and demand for this dazzling product that kilns and studios began to spring up outside of Satsuma Province, all producing Satsuma “type” wares. This does somewhat confuse the precise definition of Satsuma, but these outside kilns are generally accepted within the modern collectors generic definition. Indeed many of these “outside” studios went on to become some of the most famous for example Kinkozan in Kyoto and Yabu Meizan in Osaka.

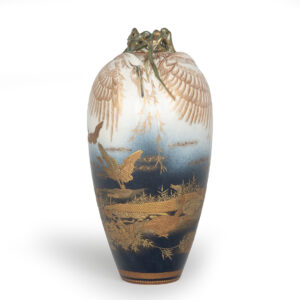

Towards the end of the Meiji period and into the Taisho period we can see a significant shift in design and especially the artistry driven perhaps by two factors. Firstly, in the early 20thC Japanese art forms began to come in for some criticism at the World Trade Fairs. Some critics began to say that it had become too fussy and stale with little innovation in design – too “over elaborate”. This would have co-incided with a growing realisation that these art works were very expensive to produce and that assumes that studios could even find enough talented painters to sustain production. As a result, the designs and outputs from some studios became much simpler with fewer or often no decorative borders and a more sparse “artistic” appearance. This is most noticeable in the late productions of the most famous Yabu Meizan studio where exquisitely detailed works gave way to simple depictions of birds in autumn maple trees and similar. Interestingly this shift in taste can also be seen in the work of the most famous cloisonné maker – Namikawa Yasuyuki.

In Satsuma earthenware we can see an art form that developed from simple (but high quality) domestic wares into breathtakingly detailed exquisitely painted works of art finally reverting back to a far more artistically simple product.

In the end it must be left to the personal tastes of the collector to determine what enters his cabinet of treasures!

Quality

Satsuma is found in a bewildering range of objects, subjects and qualities and is one of the most popularly collected of Japanese Meiji period art forms.

Interestingly most of the very finest pieces are of a modest size, often around 6 inches in height or frequently less. The finest work did come in larger sizes but they are the exception and thus rare and highly desirable.

Some makers’ output could vary dramatically in quality from the very finest of pieces destined for the wealthy connoisseur through to lower qualities aimed at more of a mass export market. Many studios had a variety of qualities all in parallel production. The best example is Kinkozan who had a small number of superb artists (the best of which is generally accepted to be Sozan) working in peaceful seclusion producing a very small number of truly exquisite works, probably the most highly detailed and enamelled the world has ever seen. At the same time in another area of the factory were mid range artisans producing mid range items, still of fine quality but not as demanding as the aforesaid. Finally items were produced that could at best be described as tourist souvenirs aimed at a mass market.

The ideal way to judge quality is to understand what the best pieces look like. Try and study fine pieces by Kinkozan, Meizan, Yabu Meizan, Seikozan, Hankinzan, Ryozan, Shoko Takebe and similar. Look at the detail, the humour and artistry captured in the designs and subjects, the crispness and lustre of the gilding, the complexity of the borders. Some works will require a magnifying glass to appreciate the supreme ability of the painter. As always the best way to judge quality is to handle as much material as possible, visit museums, sales and exhibitions and study the excellent reference books that are available. Ultimately however beauty is often in the eye of the beholder.

Condition and Damage

Satsuma earthenware is, in common with all ceramics, extremely vulnerable to damage. This can manifest itself as small scratches, cracks and chips often on rims and feet or wear to the gilding and enamels right through to major damage where items simply get smashed. It is impossible to repair and re-fire these items and thus they cannot be returned to their original perfect sumptuous condition. Restoration usually involves gluing and filling damaged areas that are then airbrushed and hand painted to match the existing enamel decoration. There are many highly skilled ceramic restorers who can dramatically improve the appearance of a damaged piece, but it will always remain imperfect and restoration is usually visible to the trained naked eye.

Accepting damage and restoration is a matter of personal choice, however I choose not to sell damaged or restored ceramics.

Perfect pieces will always be more desirable and will command far higher prices. However some minor damage on a masterpiece by Sozan for instance may be perfectly tolerable whereas the same damage on a lesser piece would render it undesirable. It is all a question of degree of damage balanced against the quality, rarity and value of a given work, and in the end only the collector can decide what is acceptable.

General advice is to buy from reliable trustworthy sources who will stand by all attributions, signatures and condition reports until such time as the collector is totally confident in his own judgement and knowledge. A lasting relationship with a trusted dealer can prove invaluable in sourcing these increasingly rare objects.

Signatures

It is a certainty that any signed piece will be far more desirable than the same piece unsigned but thankfully the vast majority of Satsuma is reliably signed. This is a refreshing and reassuring feature of collecting these beautiful works of art. The excellent reference books available illustrate hundreds of fine pieces together with the signatures and seals of most of the commonly encountered makers.

Some of the finest pieces are often signed not only by the studio but also by the artist who decorated them. These additional signatures or seals can be found on superb works from the Kinkozan studio where the artists mark is often subtly located within the actual design work itself.

Value

There is a well-known saying “something is worth what someone will pay” – and in truth that applies perfectly to these wonderful ceramics.

Certainly works by top artists and studios such as those mentioned in the “Quality” notes above were rare and very expensive when they were made! The same applies now. These masterpieces represent the pinnacle of this art form and are sought by wealthy collectors world-wide. They therefore command very high prices.

However in my opinion there are many high quality works that sit just below the finest pieces and represent staggering value for money.

Needless to say damage has a very dramatic effect on value. Damage on a superb masterpiece can bring the piece within the collecting range of many and may even make it a useful study item …again it is a matter of personal choice.

It is my contention however that a few better things are always preferable to a high volume of lesser items!

Showing all 15 resultsSorted by price: high to low

Filter Your Results

Highly skilled Japanese artisans have been producing exquisite Ceramics using a variety of techniques and in widely differing styles for many centuries. Their innovative and highly artistic output, often of staggering quality, has always been greatly treasured not only within the domestic market but also by collectors and connoisseurs worldwide.

Early porcelain from the Arita, Nabeshima, Hirado and Kutani kilns together with the refined outputs of the Kakiemon family found a ready market in the country houses of the European nobility. These early porcelains from the 17th and 18th centuries, often of impressively large size, form a specialist collecting field of their own ,but latterly it is the truly breath-taking and superbly enamelled Meiji period earthenware known as “Satsuma” that has come to be the most coveted and highly collected of all Japanese ceramics.It is for this reason that we concentrate our article on Satsuma earthenware although most of the tips and advice in this section would apply equally across the entire spectrum of Japanese ceramics.

From a purely technical point of view Japanese “Satsuma” can be described as a dense cream coloured earthenware body having a fine and even crackle glaze usually decorated in over-glaze enamels. From an artistic point of view it could easily be described as the most intricate enamelled ceramic ever made by man. As the name suggests it was originally produced in the Province of Satsuma under the patronage of the Shimazu family who had been the Daimyo there since 1615.

Its evolution into the finely decorated items that are nowadays so popular with discerning collectors did not really commence until the mid 19th century and subsequently developed rapidly during the Meiji period. Prior to that Satsuma ware enjoyed a reputation as a fine quality but frequently undecorated glazed earthenware aimed at the Japanese domestic market. However the aforesaid Daimyo of Satsuma, generally regarded as the most powerful at the time, was instrumental in Japan exhibiting at the first World Fair – the Paris Exposition in 1867 – and this naturally ensured a substantial display of high quality ceramics from his home Province. This proved to be a strong catalyst for innovation in production, design and artistic quality.

Japanese art including ceramics unsurprisingly received worldwide acclaim at the Paris Fair and indeed at subsequent exhibitions. This and several other factors quickly contributed to an explosion of interest in the “never before seen” art form that is Satsuma earthenware. Thankfully the Meiji Emperor was a great patron of Japanese Arts in all their various forms and quickly realised that the foreign currency flowing into the country from the sale of these works would greatly assist in his modernisation programme. Also many high ranking foreign advisors and their supporting workforces together with a high number of curious and wealthy early tourists were now in Japan. Satsuma ware with its developing designs and superb artistry appealed greatly to this new customer base and demand grew strongly. The continued involvement of the astute and powerful Shimazu family gave further impetus to its production.

Artistic Development

The development of Satsuma progressed hand in hand with the rapid modernisation of Japan during the Meiji period.

Early functional domestic pieces often with little or no decoration quickly evolved into a wider range of items of all shapes and sizes. Bowls, koro, vases, and boxes all became subjects for unbelievably intricate and detailed enamelling. They were adorned with finely painted and often idealised scenes from nature or rural everyday life, historical and legendary events, famous places, in fact anything that was shown to appeal to the insatiable foreign market now established both in Japan and worldwide. The lavish use of high quality gilding gave items a rich and sumptuous appearance. Decorative borders became an art form in their own right again displaying brocades, floral and other designs in a detail that defies belief.

Such was the success of and demand for this dazzling product that kilns and studios began to spring up outside of Satsuma Province, all producing Satsuma “type” wares. This does somewhat confuse the precise definition of Satsuma, but these outside kilns are generally accepted within the modern collectors generic definition. Indeed many of these “outside” studios went on to become some of the most famous for example Kinkozan in Kyoto and Yabu Meizan in Osaka.

Towards the end of the Meiji period and into the Taisho period we can see a significant shift in design and especially the artistry driven perhaps by two factors. Firstly, in the early 20thC Japanese art forms began to come in for some criticism at the World Trade Fairs. Some critics began to say that it had become too fussy and stale with little innovation in design – too “over elaborate”. This would have co-incided with a growing realisation that these art works were very expensive to produce and that assumes that studios could even find enough talented painters to sustain production. As a result, the designs and outputs from some studios became much simpler with fewer or often no decorative borders and a more sparse “artistic” appearance. This is most noticeable in the late productions of the most famous Yabu Meizan studio where exquisitely detailed works gave way to simple depictions of birds in autumn maple trees and similar. Interestingly this shift in taste can also be seen in the work of the most famous cloisonné maker – Namikawa Yasuyuki.

In Satsuma earthenware we can see an art form that developed from simple (but high quality) domestic wares into breathtakingly detailed exquisitely painted works of art finally reverting back to a far more artistically simple product.

In the end it must be left to the personal tastes of the collector to determine what enters his cabinet of treasures!

Quality

Satsuma is found in a bewildering range of objects, subjects and qualities and is one of the most popularly collected of Japanese Meiji period art forms.

Interestingly most of the very finest pieces are of a modest size, often around 6 inches in height or frequently less. The finest work did come in larger sizes but they are the exception and thus rare and highly desirable.

Some makers’ output could vary dramatically in quality from the very finest of pieces destined for the wealthy connoisseur through to lower qualities aimed at more of a mass export market. Many studios had a variety of qualities all in parallel production. The best example is Kinkozan who had a small number of superb artists (the best of which is generally accepted to be Sozan) working in peaceful seclusion producing a very small number of truly exquisite works, probably the most highly detailed and enamelled the world has ever seen. At the same time in another area of the factory were mid range artisans producing mid range items, still of fine quality but not as demanding as the aforesaid. Finally items were produced that could at best be described as tourist souvenirs aimed at a mass market.

The ideal way to judge quality is to understand what the best pieces look like. Try and study fine pieces by Kinkozan, Meizan, Yabu Meizan, Seikozan, Hankinzan, Ryozan, Shoko Takebe and similar. Look at the detail, the humour and artistry captured in the designs and subjects, the crispness and lustre of the gilding, the complexity of the borders. Some works will require a magnifying glass to appreciate the supreme ability of the painter. As always the best way to judge quality is to handle as much material as possible, visit museums, sales and exhibitions and study the excellent reference books that are available. Ultimately however beauty is often in the eye of the beholder.

Condition and Damage

Satsuma earthenware is, in common with all ceramics, extremely vulnerable to damage. This can manifest itself as small scratches, cracks and chips often on rims and feet or wear to the gilding and enamels right through to major damage where items simply get smashed. It is impossible to repair and re-fire these items and thus they cannot be returned to their original perfect sumptuous condition. Restoration usually involves gluing and filling damaged areas that are then airbrushed and hand painted to match the existing enamel decoration. There are many highly skilled ceramic restorers who can dramatically improve the appearance of a damaged piece, but it will always remain imperfect and restoration is usually visible to the trained naked eye.

Accepting damage and restoration is a matter of personal choice, however I choose not to sell damaged or restored ceramics.

Perfect pieces will always be more desirable and will command far higher prices. However some minor damage on a masterpiece by Sozan for instance may be perfectly tolerable whereas the same damage on a lesser piece would render it undesirable. It is all a question of degree of damage balanced against the quality, rarity and value of a given work, and in the end only the collector can decide what is acceptable.

General advice is to buy from reliable trustworthy sources who will stand by all attributions, signatures and condition reports until such time as the collector is totally confident in his own judgement and knowledge. A lasting relationship with a trusted dealer can prove invaluable in sourcing these increasingly rare objects.

Signatures

It is a certainty that any signed piece will be far more desirable than the same piece unsigned but thankfully the vast majority of Satsuma is reliably signed. This is a refreshing and reassuring feature of collecting these beautiful works of art. The excellent reference books available illustrate hundreds of fine pieces together with the signatures and seals of most of the commonly encountered makers.

Some of the finest pieces are often signed not only by the studio but also by the artist who decorated them. These additional signatures or seals can be found on superb works from the Kinkozan studio where the artists mark is often subtly located within the actual design work itself.

Value

There is a well-known saying “something is worth what someone will pay” – and in truth that applies perfectly to these wonderful ceramics.

Certainly works by top artists and studios such as those mentioned in the “Quality” notes above were rare and very expensive when they were made! The same applies now. These masterpieces represent the pinnacle of this art form and are sought by wealthy collectors world-wide. They therefore command very high prices.

However in my opinion there are many high quality works that sit just below the finest pieces and represent staggering value for money.

Needless to say damage has a very dramatic effect on value. Damage on a superb masterpiece can bring the piece within the collecting range of many and may even make it a useful study item …again it is a matter of personal choice.

It is my contention however that a few better things are always preferable to a high volume of lesser items!