Japanese Okimono

Okimono can be loosely translated as “object for display” or “standing object” but is more easily understood if described as a “decorative sculpture”. The subject matter can be absolutely anything,...

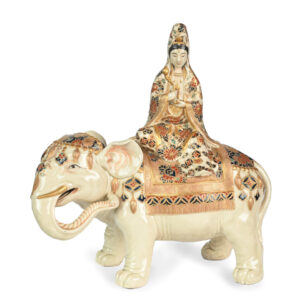

Okimono can be loosely translated as “object for display” or “standing object” but is more easily understood if described as a “decorative sculpture”. The subject matter can be absolutely anything, figural, animal, mythical, floral, avian….and that is one of the immense pleasures that Okimono gives us!

Mention the word Okimono and we immediately imagine an ivory object but the word also encompasses wonderful works of art that are commonly carved from many native Japanese woods, various metals, alloys, marine ivory and lacquer. In addition, Okimono are also frequently fashioned from more than one material, a commonly encountered example is ivory in conjunction with boxwood.

Prior to the Meiji Restoration the art of carving anything substantial was largely restricted to sculptures of a religious nature. These were produced by highly skilled artists whose family tradition often went back countless generations. Their work was mostly destined for the many Shrines and Temples throughout the land although doubtless special commissions were received from both the Imperial Household and governing Samurai families.

Historically any carvings of a “non-religious” nature tended to be Netsuke – the miniature works of art designed to hold an inro securely in the Obi of traditional Japanese clothing. These small but beautiful works of art are generally too small to be classified as Okimono and in any event were primarily functional.

And so we arrive at the Meiji Restoration with Japan having a well established history of superb carvers going back hundreds of years. Many carvers were active all over Japan but with a higher concentration naturally around the major towns and cities.

The Meiji period ushered in some dramatic changes that had an equally dramatic effect on artist carvers. Japan was fast becoming “Westernised” in nearly every way. This not only affected the structures of government and society but everyday life as well. Western styles of dress became highly fashionable for both men and women. Many temples and shrines were closed as religious beliefs and customs changed. These were exciting vibrant times for many especially in the new capital Tokyo, but conversely unsettling and worrying times for others.

The decline in traditional dress had the effect of drastically reducing the demand for Netsuke which had no place on the new Western clothing. Likewise the closing of temples had a marked effect on the religious carvers as demand plummeted. These artists found themselves in a similar position to the metalworkers of the age – becoming somewhat redundant.

However at the same time Japans’ participation in numerous worldwide art Expositions, Fairs and Exhibitions was showcasing the remarkable talents of Japanese craftsmen. The western world was amazed at the incredible quality and refinement on show within the glittering halls and pavillons of these spectacular events. Interest and demand skyrocketed both in Japan and abroad for nearly all of the Japanese arts including carvings.

Those interested in Netsuke could enjoy a ready supply of high quality old treasures now surplus to requirements and many fine collections were formed during the Meiji period. However such was the demand for carvings generally that a new market opened up at just the right time for the many carvers who had concerns for their future. Netsuke production moved swiftly and seamlessly into Okimono carving. In reality the only real differences between the two are that generally Okimono are larger and don’t need the himotoshi or holes to hold the inro cords.

As demand for these “new” carvings grew so did the number of artists producing them. New “schools” of carving emerged where talented pupils were taught by experienced masters The most notable of these was the Tokyo School of Art that opened in 1889. The most famous and talented carver that ever lived, Ishikawa Komei became a professor at this school teaching a new generation of carvers in a somewhat different style. The output from this school were often large one piece figural ivory okimono of staggering realism and detail.

Other schools and studios concentrated on smaller intricate pieces, often more akin to the style of netsuke. Sometimes it can be difficult to say definitively whether a piece is a large late netsuke or a small okimono!

Demand continued to increase dramatically and to fill it more and more carvers emerged. The Government continued to encourage and support the industry as the flow of foreign currency into Japan was helping the modernisation programme.

A major drawback however was that the finest of these works of art could literally take years to complete so it was inevitable that in order to meet the demand, quality eventually began to deteriorate in favour of rapid production. Thankfully masterpieces did continue to be made by the truly dedicated artists who in turn became famous and often wealthy as a result.

Materials

In my experience excluding bronze and other metal sculptures (which are cast rather than carved) I would say that roughly 75% of Okimono are carved from elephant ivory. This is viewed as a contentious issue in some countries nowadays. In my view it is important to remember that these fabulous works of art (not just Japanese but Chinese, European, Indian etc) were produced over a hundred years or more ago in an age when little regard was paid to conservation and conscience. Standards and beliefs were vastly different to our modern enlightened attitudes. I believe we should enjoy these superb works of art for what they are – treasures from a long lost time and a long lost place – Meiji era Japan.

Of the remaining 25% I would say 15% are fashioned from various woods and the remaining 10% comprising marine ivory, lacquer and more seldom used materials. These figures are not to be treated as 100% accurate but merely as a guide to what the collector can expect to encounter.

As mentioned, bronze and other metals are used to produce Okimono but here the production method is totally different. The most commonly employed process for metal is the “lost wax” method whereby the subject is carved in wax and then cast from a mould taken from the wax model.

Quality

As with all works of art, Japanese Okimono come in a wide range of subjects, sizes and qualities.

They vary from the very finest pieces destined for the wealthy connoisseur (and these are truly breathtaking) through to superb middle range pieces and on to a lower quality product destined for more of a mass export market.

The best way to judge quality is to handle as much material as possible, visit museums, sales and exhibitions and study any reference book available ((((LINK???))). Beauty is often in the eye of the beholder!

A few tips to look out for are the details and expression that are conveyed in faces – the presence of teeth in an open mouth, obvious humour or suffering or anger or old age. Also the realism of feet, toenails, tendons etc. Hands are notoriously difficult to carve so look for fingernails, power in a mans’ grip or delicacy in a ladys’. Hidden musculature beneath clothing or the delicacy of decoration on Kimono. Seek out the finest pieces – this gives the collector something to compare to.

Condition and damage

As with any work of art, condition always has a bearing on its desirability and value. By the very nature of the material (excluding metalwork) Okimono can be very susceptible to everyday knocks and damage. Wood and ivory are easily chipped and broken especially those intricate items with many vulnerable protruberances. In skilled hands minor chips can often be removed and years of grime cleaned away but I would counsel against acquiring anything that has obvious major damage.

Also, being natural materials, wood and ivory can be prone to cracking as a result of atmospheric changes – too dry, too hot etc.

By no means does this mean that all works are damaged – far from it. Many Okimono have been treasured and cosseted for generations within collections and are perfectly preserved with only minor inevitable age defects. Having survived for over a hundred years it is unlikely that any further deterioration would occur unless they are subjected to extremes of heat or dryness. Age related hairlines, provided they are not extensive or excessive are usually unobtrusive and perfectly acceptable.

Signatures

It is a certainty that any signed piece will be far more desirable than the same piece unsigned but thankfully the vast majority of Okimono of all types, styles and subjects are reliably signed. This is a refreshing and reassuring feature of collecting Okimono. Reference books on the subject are available but none could ever hope to cover the many hundreds, possibly thousands of artists of all schools and qualities who plied their trade during this remarkable explosion of carving.

General advice is to buy from reliable trustworthy sources who will stand by all attributions, signatures and condition reports until such time as the collector is totally confident in his own judgement and knowledge.

Value

There is a well-known saying “something is worth what someone will pay” – and in truth nowadays that applies perfectly to these wonderful works.

Certainly pieces by artists such as Ishikawa Komei, Hokyudo Itsumin, Masanao of Yamada, Masakazu of Nagoya and similar, together with their star pupils were rare and very expensive when they were made! These masterpieces represent the pinnacle of this art form and are sought by wealthy collectors world-wide. They therefore command very high prices.

However In my opinion there are many high quality works that sit just below the finest pieces and represent staggering value for money. Thankfully it is still possible to form a collection of superb work by these numerous artists for an outlay that looks very modest bearing in mind the time it took to produce them and the sheer quality and artistry.

As with all forms of Japanese Art it is my contention however that a few better things are always preferable to a high volume of lesser items!

Showing all 8 resultsSorted by price: high to low

Filter Your Results

Okimono can be loosely translated as “object for display” or “standing object” but is more easily understood if described as a “decorative sculpture”. The subject matter can be absolutely anything, figural, animal, mythical, floral, avian….and that is one of the immense pleasures that Okimono gives us!

Mention the word Okimono and we immediately imagine an ivory object but the word also encompasses wonderful works of art that are commonly carved from many native Japanese woods, various metals, alloys, marine ivory and lacquer. In addition, Okimono are also frequently fashioned from more than one material, a commonly encountered example is ivory in conjunction with boxwood.

Prior to the Meiji Restoration the art of carving anything substantial was largely restricted to sculptures of a religious nature. These were produced by highly skilled artists whose family tradition often went back countless generations. Their work was mostly destined for the many Shrines and Temples throughout the land although doubtless special commissions were received from both the Imperial Household and governing Samurai families.

Historically any carvings of a “non-religious” nature tended to be Netsuke – the miniature works of art designed to hold an inro securely in the Obi of traditional Japanese clothing. These small but beautiful works of art are generally too small to be classified as Okimono and in any event were primarily functional.

And so we arrive at the Meiji Restoration with Japan having a well established history of superb carvers going back hundreds of years. Many carvers were active all over Japan but with a higher concentration naturally around the major towns and cities.

The Meiji period ushered in some dramatic changes that had an equally dramatic effect on artist carvers. Japan was fast becoming “Westernised” in nearly every way. This not only affected the structures of government and society but everyday life as well. Western styles of dress became highly fashionable for both men and women. Many temples and shrines were closed as religious beliefs and customs changed. These were exciting vibrant times for many especially in the new capital Tokyo, but conversely unsettling and worrying times for others.

The decline in traditional dress had the effect of drastically reducing the demand for Netsuke which had no place on the new Western clothing. Likewise the closing of temples had a marked effect on the religious carvers as demand plummeted. These artists found themselves in a similar position to the metalworkers of the age – becoming somewhat redundant.

However at the same time Japans’ participation in numerous worldwide art Expositions, Fairs and Exhibitions was showcasing the remarkable talents of Japanese craftsmen. The western world was amazed at the incredible quality and refinement on show within the glittering halls and pavillons of these spectacular events. Interest and demand skyrocketed both in Japan and abroad for nearly all of the Japanese arts including carvings.

Those interested in Netsuke could enjoy a ready supply of high quality old treasures now surplus to requirements and many fine collections were formed during the Meiji period. However such was the demand for carvings generally that a new market opened up at just the right time for the many carvers who had concerns for their future. Netsuke production moved swiftly and seamlessly into Okimono carving. In reality the only real differences between the two are that generally Okimono are larger and don’t need the himotoshi or holes to hold the inro cords.

As demand for these “new” carvings grew so did the number of artists producing them. New “schools” of carving emerged where talented pupils were taught by experienced masters The most notable of these was the Tokyo School of Art that opened in 1889. The most famous and talented carver that ever lived, Ishikawa Komei became a professor at this school teaching a new generation of carvers in a somewhat different style. The output from this school were often large one piece figural ivory okimono of staggering realism and detail.

Other schools and studios concentrated on smaller intricate pieces, often more akin to the style of netsuke. Sometimes it can be difficult to say definitively whether a piece is a large late netsuke or a small okimono!

Demand continued to increase dramatically and to fill it more and more carvers emerged. The Government continued to encourage and support the industry as the flow of foreign currency into Japan was helping the modernisation programme.

A major drawback however was that the finest of these works of art could literally take years to complete so it was inevitable that in order to meet the demand, quality eventually began to deteriorate in favour of rapid production. Thankfully masterpieces did continue to be made by the truly dedicated artists who in turn became famous and often wealthy as a result.

Materials

In my experience excluding bronze and other metal sculptures (which are cast rather than carved) I would say that roughly 75% of Okimono are carved from elephant ivory. This is viewed as a contentious issue in some countries nowadays. In my view it is important to remember that these fabulous works of art (not just Japanese but Chinese, European, Indian etc) were produced over a hundred years or more ago in an age when little regard was paid to conservation and conscience. Standards and beliefs were vastly different to our modern enlightened attitudes. I believe we should enjoy these superb works of art for what they are – treasures from a long lost time and a long lost place – Meiji era Japan.

Of the remaining 25% I would say 15% are fashioned from various woods and the remaining 10% comprising marine ivory, lacquer and more seldom used materials. These figures are not to be treated as 100% accurate but merely as a guide to what the collector can expect to encounter.

As mentioned, bronze and other metals are used to produce Okimono but here the production method is totally different. The most commonly employed process for metal is the “lost wax” method whereby the subject is carved in wax and then cast from a mould taken from the wax model.

Quality

As with all works of art, Japanese Okimono come in a wide range of subjects, sizes and qualities.

They vary from the very finest pieces destined for the wealthy connoisseur (and these are truly breathtaking) through to superb middle range pieces and on to a lower quality product destined for more of a mass export market.

The best way to judge quality is to handle as much material as possible, visit museums, sales and exhibitions and study any reference book available ((((LINK???))). Beauty is often in the eye of the beholder!

A few tips to look out for are the details and expression that are conveyed in faces – the presence of teeth in an open mouth, obvious humour or suffering or anger or old age. Also the realism of feet, toenails, tendons etc. Hands are notoriously difficult to carve so look for fingernails, power in a mans’ grip or delicacy in a ladys’. Hidden musculature beneath clothing or the delicacy of decoration on Kimono. Seek out the finest pieces – this gives the collector something to compare to.

Condition and damage

As with any work of art, condition always has a bearing on its desirability and value. By the very nature of the material (excluding metalwork) Okimono can be very susceptible to everyday knocks and damage. Wood and ivory are easily chipped and broken especially those intricate items with many vulnerable protruberances. In skilled hands minor chips can often be removed and years of grime cleaned away but I would counsel against acquiring anything that has obvious major damage.

Also, being natural materials, wood and ivory can be prone to cracking as a result of atmospheric changes – too dry, too hot etc.

By no means does this mean that all works are damaged – far from it. Many Okimono have been treasured and cosseted for generations within collections and are perfectly preserved with only minor inevitable age defects. Having survived for over a hundred years it is unlikely that any further deterioration would occur unless they are subjected to extremes of heat or dryness. Age related hairlines, provided they are not extensive or excessive are usually unobtrusive and perfectly acceptable.

Signatures

It is a certainty that any signed piece will be far more desirable than the same piece unsigned but thankfully the vast majority of Okimono of all types, styles and subjects are reliably signed. This is a refreshing and reassuring feature of collecting Okimono. Reference books on the subject are available but none could ever hope to cover the many hundreds, possibly thousands of artists of all schools and qualities who plied their trade during this remarkable explosion of carving.

General advice is to buy from reliable trustworthy sources who will stand by all attributions, signatures and condition reports until such time as the collector is totally confident in his own judgement and knowledge.

Value

There is a well-known saying “something is worth what someone will pay” – and in truth nowadays that applies perfectly to these wonderful works.

Certainly pieces by artists such as Ishikawa Komei, Hokyudo Itsumin, Masanao of Yamada, Masakazu of Nagoya and similar, together with their star pupils were rare and very expensive when they were made! These masterpieces represent the pinnacle of this art form and are sought by wealthy collectors world-wide. They therefore command very high prices.

However In my opinion there are many high quality works that sit just below the finest pieces and represent staggering value for money. Thankfully it is still possible to form a collection of superb work by these numerous artists for an outlay that looks very modest bearing in mind the time it took to produce them and the sheer quality and artistry.

As with all forms of Japanese Art it is my contention however that a few better things are always preferable to a high volume of lesser items!